The road is long, with many a winding turn

That leads us to who knows where, who knows when.

But I’m strong, strong enough to carry him.

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother.

… So on we go. His welfare is of my concern.

No burden is he to bear. We’ll get there.

… For I know he would not encumber me.

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother.

– Bob Russell & Bobby Scott, from “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” (1969)

Ever since my Thomas took me to meet Jesus last April on the third level of the astral plane, I have been thinking about the profound symbolism of all those neon-colored fish. As Jesus told me His personal story, He sat with Thomas and me side by side on a riverbank while deer grazed behind us, and we fed His fish with grain that just appeared in our hands. More symbolism. And why should anyone care that Jesus has chosen to live so simply now? Why should it be important that Jesus even has a backstory? Why isn’t it enough for us to just start a website to teach the Lord’s Gospel words to people who want to begin a closer walk with Him? To be frank with you, I got to the point by early May of trying to pretend it hadn’t even happened. It had all been just a dream, right? And Jesus now doesn’t want to look like church-Jesus? Come on! He has been hanging with my spirit guide for six thousand years? Everyone else sees Jesus as God Incarnate with a halo around His head, while in our little world He’s just a part of the family?

Ever since my Thomas took me to meet Jesus last April on the third level of the astral plane, I have been thinking about the profound symbolism of all those neon-colored fish. As Jesus told me His personal story, He sat with Thomas and me side by side on a riverbank while deer grazed behind us, and we fed His fish with grain that just appeared in our hands. More symbolism. And why should anyone care that Jesus has chosen to live so simply now? Why should it be important that Jesus even has a backstory? Why isn’t it enough for us to just start a website to teach the Lord’s Gospel words to people who want to begin a closer walk with Him? To be frank with you, I got to the point by early May of trying to pretend it hadn’t even happened. It had all been just a dream, right? And Jesus now doesn’t want to look like church-Jesus? Come on! He has been hanging with my spirit guide for six thousand years? Everyone else sees Jesus as God Incarnate with a halo around His head, while in our little world He’s just a part of the family?

But my Thomas is such a practical man. I was going through what felt like stages of grief, and he handled it so matter of factly. When I was in the “Why me?” stage, he said patiently, repeatedly, “Why not you?” When I was in the “It was just a dream” stage, he would bring moments from that amazing night to my mind again, and in such detail that I knew freshly that of course it had not been a dream. Then when I stopped denying it sometime in July, and I finally began to try to make sense of what seems to be unfolding in my life, he was patient with me about that as well. He has lived this truth for six thousand years, and although incarnational amnesia blocks it for me temporarily, I have come to accept on an intellectual level that I have lived it with him and with Jesus for a third of that time. Thomas should long since have become a perfected being himself, but he has chosen instead to stay with Jesus. And he tells me that I have made a similar choice, although of course I have no memory of that while I am in a body.

What is most interesting is what I now understand is true about Jesus. When He ascended after His resurrection, He chose not to join the Godhead Collective or to go even higher, but rather He wanted to remain on the entrance level of the astral plane. The standard route for all of humankind is to endlessly elevate our spiritual vibrations through repeated incarnations. And as we do that, we rise gradually higher, and we add our energies to the various collectives, melding more and more, until eventually we achieve the perfection of level seven, at which point we can merge with the Godhead Collective. Or else we might choose to elevate ourselves even above the Godhead level, as Jesus easily could do, since He is vibrating even higher than the Godhead Collective. But these choices are irrevocable. Once you merge with the Godhead Collective or you elevate beyond it, there can be no coming back. And Jesus loves people! He loves people so much that He vowed long ago that He was going to stay with us and teach us until every last one of us is elevated. And His vow is beyond just an oath at this point. It has become His central joy. It is the core of who He is.

What is most interesting is what I now understand is true about Jesus. When He ascended after His resurrection, He chose not to join the Godhead Collective or to go even higher, but rather He wanted to remain on the entrance level of the astral plane. The standard route for all of humankind is to endlessly elevate our spiritual vibrations through repeated incarnations. And as we do that, we rise gradually higher, and we add our energies to the various collectives, melding more and more, until eventually we achieve the perfection of level seven, at which point we can merge with the Godhead Collective. Or else we might choose to elevate ourselves even above the Godhead level, as Jesus easily could do, since He is vibrating even higher than the Godhead Collective. But these choices are irrevocable. Once you merge with the Godhead Collective or you elevate beyond it, there can be no coming back. And Jesus loves people! He loves people so much that He vowed long ago that He was going to stay with us and teach us until every last one of us is elevated. And His vow is beyond just an oath at this point. It has become His central joy. It is the core of who He is.

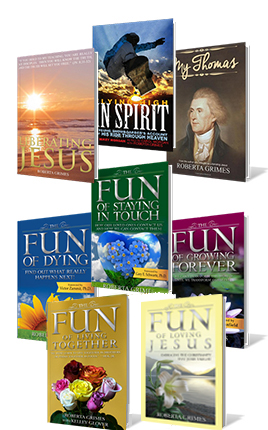

I am writing about Jesus intimately, so I should add that I write at His request. Jesus has come to see after He and Thomas and some few others of His circle have done a lot of talking about this that while a figure named “Jesus” has achieved ultimate fame on earth, that figure was shaped by Roman Christianity and is just a kind of magical Creature at this point, altogether disassociated from what Jesus taught. And knowing that bothers Jesus very much. So at His further request, we will be telling Jesus’s personal story in The Fun of Loving Jesus and on teachingsbyjesus.com. And the book is about to go to press. The website will be up by March.

You would think that it would be a simple matter for Jesus to maintain His humanity, but it is not. The fact is that all of us are aspects of Consciousness. So all of us are aspects of God exploring the human experience, and our natural cycle is to rise ever higher. Which means that for Jesus to remain in any way human when He is at the same time even above the Godhead Collective level in spiritual development is an experiment with Consciousness that needs constant maintenance. And that is in large part what His close relationship with Thomas seems at this point to be about. My Thomas calls his role for Jesus “balance.” He spends so much time talking with Jesus, teasing Him, even mocking Him sometimes, playing with Him, just whatever it might take to help Jesus maintain His solid human grounding. It shocked me at first to see how disrespectful Thomas could be to Jesus, but that is what the Lord wants from him. He gets nothing but worship otherwise. And worship is the very last thing He wants! But at least his pet fish and his deer don’t worship Him. The aborted children see Him as just some version of a doting Uncle, and even the Lord’s elevated energy seems to be only normal to all those gleeful toddlers, who giggle and play as they climb all over Him. Even the older children gladly crowd around what is almost the only father figure they have. Jesus is doing all that He can as God to maintain Himself as also human.

You would think that it would be a simple matter for Jesus to maintain His humanity, but it is not. The fact is that all of us are aspects of Consciousness. So all of us are aspects of God exploring the human experience, and our natural cycle is to rise ever higher. Which means that for Jesus to remain in any way human when He is at the same time even above the Godhead Collective level in spiritual development is an experiment with Consciousness that needs constant maintenance. And that is in large part what His close relationship with Thomas seems at this point to be about. My Thomas calls his role for Jesus “balance.” He spends so much time talking with Jesus, teasing Him, even mocking Him sometimes, playing with Him, just whatever it might take to help Jesus maintain His solid human grounding. It shocked me at first to see how disrespectful Thomas could be to Jesus, but that is what the Lord wants from him. He gets nothing but worship otherwise. And worship is the very last thing He wants! But at least his pet fish and his deer don’t worship Him. The aborted children see Him as just some version of a doting Uncle, and even the Lord’s elevated energy seems to be only normal to all those gleeful toddlers, who giggle and play as they climb all over Him. Even the older children gladly crowd around what is almost the only father figure they have. Jesus is doing all that He can as God to maintain Himself as also human.

So His brother relationship with Thomas seems to feel very important to Jesus. My Thomas was Jesus’s elder brother in their earth-lifetimes that ended in a war almost six thousand years ago, but still their relationship is so tight that when you see them together their bond is clear. When Jesus first set out to call His disciples at the start of His public ministry on earth, He even called pairs of brothers.

“Now as Jesus was walking by the Sea of Galilee, He saw two brothers, Simon, who was called Peter, and his brother Andrew, casting a net into the sea; for they were fishermen. And He said to them, ‘Follow Me, and I will make you fishers of people.’ Immediately they left their nets and followed Him. Going on from there He saw two other brothers, James the son of Zebedee, and his brother John, in the boat with their father Zebedee, mending their nets; and He called them. Immediately they left the boat and their father, and followed Him.” (MT 4:18-22) So Jesus first called pairs of brothers. And John, the brother of James, was actually Jesus’s younger brother from the same earth-lifetime that they both had shared with Thomas, while Thomas would soon also join Him in His lifetime as Jesus to be His private witness, going out often among the people and reporting back to Jesus what the people were saying about Him. I can only imagine that Jesus expected that the bonds among all those brothers would further strengthen the bonds within His band of disciples.

“Now as Jesus was walking by the Sea of Galilee, He saw two brothers, Simon, who was called Peter, and his brother Andrew, casting a net into the sea; for they were fishermen. And He said to them, ‘Follow Me, and I will make you fishers of people.’ Immediately they left their nets and followed Him. Going on from there He saw two other brothers, James the son of Zebedee, and his brother John, in the boat with their father Zebedee, mending their nets; and He called them. Immediately they left the boat and their father, and followed Him.” (MT 4:18-22) So Jesus first called pairs of brothers. And John, the brother of James, was actually Jesus’s younger brother from the same earth-lifetime that they both had shared with Thomas, while Thomas would soon also join Him in His lifetime as Jesus to be His private witness, going out often among the people and reporting back to Jesus what the people were saying about Him. I can only imagine that Jesus expected that the bonds among all those brothers would further strengthen the bonds within His band of disciples.

And what really astonishes me is my Thomas’s decision to devote his eternity to Jesus. He won’t much talk about it with me, but it is clear that from the moment that Jesus first attained the seventh afterlife level some six thousand earth-years ago, this eternal being who is now my guide – but only so we can work together on their project of re-starting the spreading of the Lord’s Gospel teachings on earth – has given himself over to serving Jesus forevermore. Even his one little foray into fame – his Thomas Jefferson lifetime – was to him mostly about creating a country where Jesus’s teachings could finally prosper. My Thomas’s love for the Man that he still calls his Brother is beyond what I can ever fathom.

So our task now is to begin to spread these Gospel teachings! And I honestly don’t know how best to do that. To become fishers of people? I have no idea. You would think that it would be an easy task, with the name of Jesus already so famous on earth, but our problem is that Jesus is famous at this point mostly for dying for our sins and then rising from the dead, all of which is beside the point. All that Jesus ever has wanted, and all that He ever wants even now, is to be our Teacher. If Jesus came to save us from anything, it was from our ignorance of the certain truth that God is loving Spirit, we are eternally part of Spirit, and we enter these brief earth-lifetimes to raise our vibrations within Spirit. Jesus’s mission was hijacked by Roman Christianity, so then His mission took a seventeen-hundred-year detour. But it remains unchanged from what it was when Jesus first charged His disciples to spread His teachings, saying, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to Me. Go, therefore, and make disciples of all the nations … teaching them to follow all that I commanded you; and behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (MT 28:18-20). As Jesus and Thomas have described their rejuvenated movement to me, it will be:

So our task now is to begin to spread these Gospel teachings! And I honestly don’t know how best to do that. To become fishers of people? I have no idea. You would think that it would be an easy task, with the name of Jesus already so famous on earth, but our problem is that Jesus is famous at this point mostly for dying for our sins and then rising from the dead, all of which is beside the point. All that Jesus ever has wanted, and all that He ever wants even now, is to be our Teacher. If Jesus came to save us from anything, it was from our ignorance of the certain truth that God is loving Spirit, we are eternally part of Spirit, and we enter these brief earth-lifetimes to raise our vibrations within Spirit. Jesus’s mission was hijacked by Roman Christianity, so then His mission took a seventeen-hundred-year detour. But it remains unchanged from what it was when Jesus first charged His disciples to spread His teachings, saying, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to Me. Go, therefore, and make disciples of all the nations … teaching them to follow all that I commanded you; and behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (MT 28:18-20). As Jesus and Thomas have described their rejuvenated movement to me, it will be:

- A movement, and not a religion. Crucially, therefore, Jesus’s new movement will be devoid of dogmas! There will be nothing that anyone is asked to believe beyond the Lord’s teachings themselves.

- Based in the four canonical Gospels. People have asked me about the other Gospels, and I think that I have read all of them, but I don’t believe that they add anything crucial. And I have been given to understand that Jesus Himself oversaw the selection at First Nicaea in the year 325 of the four Gospels that made it into the Christian Bible, which should seal that deal for us.

- Based in eradicating every fear. Fear is the opposite of love, and since spiritual growth requires that we raise our consciousness vibrations away from fear and toward love, Jesus’s website will be associated with seekreality.com, our website which teaches the truth about death and the afterlife, and which thereby helps people to eradicate the fear of death.

- Jesus intends this movement to be considered to be a new kind of Christianity. I have used many Christian hymns as frame-verses here, and with just a few words changed, even more hymns could be used. If we emphatically insist that the Lord’s movement is not a religion at all, but it is instead a living movement without dogmas and its only doctrine is Jesus’s Gospel teachings, then everyone is invited to join us and to learn from the Lord Himself what He taught.

So we begin here. We will have The Fun of Loving Jesus for our handbook, teachingsbyjesus.com as our source of the Lord’s words and our inspiration, and seekreality.com as a place to go for the eradication of all our fears. All three of these resources have been created at the Lord’s request. Jesus intends the modern-day dawning of the kingdom of God on earth to be a gradual process. His original movement had been growing for almost three hundred years and had millions of followers before the Romans under Constantine destroyed it and founded Roman Christianity in its ashes, so even though communications are rather better now than they were when Jesus sent His first followers to spread His teachings to the world, still our own role will be just to begin this work all over again, and Jesus will call others to carry it on after us. So now once again it begins!

So we begin here. We will have The Fun of Loving Jesus for our handbook, teachingsbyjesus.com as our source of the Lord’s words and our inspiration, and seekreality.com as a place to go for the eradication of all our fears. All three of these resources have been created at the Lord’s request. Jesus intends the modern-day dawning of the kingdom of God on earth to be a gradual process. His original movement had been growing for almost three hundred years and had millions of followers before the Romans under Constantine destroyed it and founded Roman Christianity in its ashes, so even though communications are rather better now than they were when Jesus sent His first followers to spread His teachings to the world, still our own role will be just to begin this work all over again, and Jesus will call others to carry it on after us. So now once again it begins!

… If I’m laden at all, I’m laden with sadness

That everyone’s heart Isn’t filled with the gladness

Of love for one another.

… It’s a long, long road, From which there is no return.

While we’re on the way to there, Why not share?

… And the load Doesn’t weigh me down at all,

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother.

– Bob Russell & Bobby Scott, from “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” (1969)