One unfortunate complication of the Scottsdale Life in the Afterlife conference in September was my fault. In an effort to help to rectify it, I am going to give you a treat!

going to give you a treat!

Victor and Wendy Zammit of Sydney, Australia, are the world’s leading experts on the afterlife evidence. Their A Lawyer Presents the Evidence for the Afterlife (2013) is an indispensable handbook for anyone who wants to grasp the breadth of the evidence that has accumulated over centuries. In the course of gathering their evidence, Victor and Wendy have investigated physical mediums all over the world; and after more than a decade of studying David Thompson, a Briton who now lives in New Zealand, they have pronounced him to be one of the three or four best physical mediums who will sit for the public. There are others who sit in private circles, but their reluctance to put themselves on public view is understandable. Physical mediumship is so dangerous that it can readily injure or even kill the medium. It has been estimated that doing very much of it will shorten a medium’s life by as much as a decade.

Actually explaining how physical mediums work, and how they differ from the spiritual mediums who are much more common, would take a book by itself. Fortunately, Wendy Zammit is writing that book, with publication planned for next summer. Suffice it to say that physical mediums generally begin as spiritual mediums. They then develop the ability to go into trance, where they produce in volume a material called ectoplasm that the dead can use to become material. They begin to produce voices, apports, and other phenomena, and generally they can put on quite a show that unfortunately the medium altogether misses because he is deep in trance throughout.

For the medium’s safety, and to maximize results, séances have to be conducted in darkness. The medium is tied to a chair inside a curtained cabinet in a room that must be altogether sealed against light and entry. Some twenty to forty sitters are in a horseshoe around three sides of the room, holding hands. Elevating the spiritual energy in the room is important, so each séance begins with loud singing. A physical medium’s séance is a production requiring vast preparation and a lot of what feels like unnecessary drama, and for clueless Americans to experience all this without careful prior education can make the more skeptical of us believe that the whole thing must be a circus sham.

My first séance with a physical medium was with David Thompson at the  Life in the Afterlife conference in September. I didn’t know what to expect, but I loved all the seeming foolishness of it: the examination and sealing of the room, the tying of David to a heavy chair, the singing and holding hands, and even the darkness. And not only did David’s usual crew materialize, including Louis Armstrong and Quentin Crisp, but there were three emotional reunions when relatives of sitters materialized and spoke to them and touched them. It was great!

Life in the Afterlife conference in September. I didn’t know what to expect, but I loved all the seeming foolishness of it: the examination and sealing of the room, the tying of David to a heavy chair, the singing and holding hands, and even the darkness. And not only did David’s usual crew materialize, including Louis Armstrong and Quentin Crisp, but there were three emotional reunions when relatives of sitters materialized and spoke to them and touched them. It was great!

Sadly, though, there always are people who delight in sowing discord. Two or three of those who had attended this séance expressed their doubts to those running the conference, which was fine. Their doubts were my fault, since I had not known enough to insist upon adequate education of the sitters beforehand. But on the morning after the séance, one mischievous fellow was glad to proclaim that David Thompson was an outright fraud. He knew this because he himself was a magician. I happened upon him expounding to others, so I overheard a lot of what he was saying; and what appalled me was not so much what he said, nor the number of people to whom he said it, but the glee he seemed to feel in assuming the role of garden-party skunk.

Here I will share an important tip. Never make Victor Zammit angry! What followed after I relayed to Victor and Wendy what our magician friend had said were days of detailed emails flying worldwide, accompanied by a demand for an apology. Victor was preparing to file a lawsuit. The necessary apology was made.

Do I believe the David Thompson séance that I attended was genuine? I do. Victor and Wendy Zammit are the foremost living afterlife researchers. They are skeptical by nature, and after long acquaintance I have found their integrity to be impeccable. They have described to me their exhaustive testing of David over 200 séances, and they have given me satisfactory explanations for every one of the “issues” that our magician friend considered to be his proof of fraud.

David Thompson doesn’t have to sit for us! He could make more money more easily, spend more time with his wife and children, and surely better protect his health by never entering trance again. What he does in continuing to perfect his abilities as a physical medium is for us, dear friends. He is putting the edification of humankind before his personal needs. And for that, I am very grateful!

I promised you a treat. Now, here it comes!

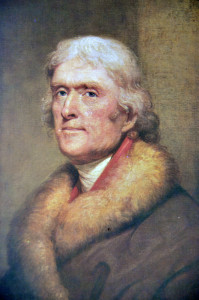

Montague Keen was a leading British afterlife expert who died  unexpectedly on January 15, 2004. He has been perhaps as active in this field postmortem as he ever was before! He has been turning up often when researchers (including yours truly) were consulting with their spirit guides, or when soul-phone experimenters were sitting at a table with the dead teams who lead their research. And shortly after his death, Monty Keen materialized at a David Thompson séance being held on May 16, 2004, in order to (among other things) talk about what should be said at his memorial service. Just click on this link for an mp3 of the event. You can hear the ectoplasm (that occasional whooshing sound), and you can hear Monty learning to figure out how to reproduce his living voice. His wife and friends have confirmed that this was incontrovertibly Montague Keen. I think this is one of the most remarkable things that I have heard in my life!

unexpectedly on January 15, 2004. He has been perhaps as active in this field postmortem as he ever was before! He has been turning up often when researchers (including yours truly) were consulting with their spirit guides, or when soul-phone experimenters were sitting at a table with the dead teams who lead their research. And shortly after his death, Monty Keen materialized at a David Thompson séance being held on May 16, 2004, in order to (among other things) talk about what should be said at his memorial service. Just click on this link for an mp3 of the event. You can hear the ectoplasm (that occasional whooshing sound), and you can hear Monty learning to figure out how to reproduce his living voice. His wife and friends have confirmed that this was incontrovertibly Montague Keen. I think this is one of the most remarkable things that I have heard in my life!

Addition: Here is another delightful mp3 of Montague Keen coming through in a David Thompson seance, this one recorded about nine months after Monty’s death. He isn’t quite as easy to understand here as he is in the other recording, but demonstrably he remains the same irrepressible man that he was in life. Toward the end of the nine minutes, he talks about David’s pending move from Britain to Australia, and he asks the sitters to suggest to David that he look up Victor Zammit. David did that, and thus began the Zammits’ decade-long study of the medium. Monty also assures the sitters that David is what he calls “the real McCoy.” Here is Monty, by courtesy of the Afterlife Research and Education Institute (AREI) and its President, our wonderful friend Dr. R. Craig Hogan. Listen!