A friend who often comments here has asked me why in this series of posts I have talked about the United States alone, when in his view it is time for Americans to become good citizens of all the world. He is precisely right! Imagine a world that has become one neighborhood, everyone watching out for everyone else, where all of humankind is united in love and we are far beyond any kind of war. But if that is the goal, how on earth can we get there?

A friend who often comments here has asked me why in this series of posts I have talked about the United States alone, when in his view it is time for Americans to become good citizens of all the world. He is precisely right! Imagine a world that has become one neighborhood, everyone watching out for everyone else, where all of humankind is united in love and we are far beyond any kind of war. But if that is the goal, how on earth can we get there?

Ever since the end of World War I, well-meaning people have wanted to put into place some sort of worldwide governance that might be able to end all wars. Not only have these efforts come to naught, but a case can be made that they actually have sharpened existing divisions among nations. The problem with our attempts to unite the world has been the fact that every one of them has been top-down! Uniting the world’s governments can be of little help if our real goal is to unite the world’s people.

The United Nations is typical. The U.N. is an assembly of governments, many of which are frank dictatorships. No attempt is made by the U.N. to lessen the depredations of the world’s worst rulers, so far from uplifting the people of the world, the United Nations gives legitimacy and support to tyrants who oppress and destroy. The U.N. might prevent a war or two, but in refusing to insist on basic human rights it makes the conditions of many still worse.

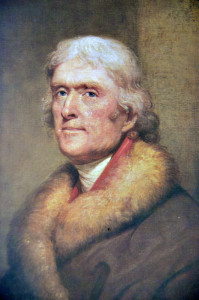

As is true of politics and religion, coalitions of governments are primarily about controlling and impoverishing people. No matter the good intentions with which political, religious, and world organizations might begin to do their work, soon they are all about funneling power and money into the hands of a few. All you need to know about Christianity is that the Catholic Church is worth at least $130 billion now, the Mormon Church is worth $200 billion, and even the Church of England is worth $7.8 billion. In America, successful politicians routinely amass great personal wealth; and even Yasser Arafat, the Palestinian hero, died a billionaire! Every bit of all this money gathered into hands at the very top came from the labor of masses of people who had been coerced into yielding it up. Thomas Jefferson memorably said that no government should “take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned,” but these numbers make a mockery of that wish! No assembly organized on the top-down model can be of any use to us as we work to build a healthier and more sustainable future for all the world.

So to answer our friend who wonders why I keep talking about the United States and I  never mention our need to be good citizens of the world, I say this: Unless we can perfect and spread the Founders’ brilliant governmental model, we are going to have no hope at all of uplifting the rest of suffering humankind.

never mention our need to be good citizens of the world, I say this: Unless we can perfect and spread the Founders’ brilliant governmental model, we are going to have no hope at all of uplifting the rest of suffering humankind.

The world over the past two hundred years has been a wondrous laboratory! Alternative forms of government have been extensively tried, so it is easy now to say what works fairly well and what cannot work at all. To judge the relative success of governmental models, we will need some objective measures. I propose these four:

- Responsiveness to the people being governed;

- An emphasis on person freedom;

- Broad-based economic prosperity; and

- Long-term internal stability and peace.

When considered in these terms, there never is going to be a perfect government. What we are seeking, therefore, is a governmental design that will make good government possible, and in that sweepstakes there is one clear winner! Any form of class-based, non-elective rule is destructive of prosperity for the masses, which is why for most of human history nearly all people have lived miserable lives. A century ago we might have thought that the high ideals inherent in collectivist models like communism and socialism stood some chance of doing better, but in practice collectivist governments have been disastrous whenever they have been tried. Just the process of collectivization in the 20th century resulted in at least a hundred million deaths, and the sort of top-down planning that collectivist governments depend on is anathema to personal happiness and an absolute barrier to real prosperity! It is only governments directed and controlled by the people being governed that make universal happiness and prosperity even possible.

And of all historical attempts at establishing government by and for the people, none has approached the long-term success and stability of the American model. Our Founders’ core insight was the fact that, as later was said by British historian Lord Acton, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” So the American Founders put all governmental power into the hands of the people, and they designed a stable, universally responsive, and remarkably resilient governmental model. The federal government of the United States has withstood every abuse that power-hungry politicians could heap upon it over the past two hundred years! It has become bloated and distorted to the point where the Founders would be appalled to see it now, but it retains at its core that perfect model that Thomas Jefferson described as ideal. He called it a design for “a wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.”

And of all historical attempts at establishing government by and for the people, none has approached the long-term success and stability of the American model. Our Founders’ core insight was the fact that, as later was said by British historian Lord Acton, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” So the American Founders put all governmental power into the hands of the people, and they designed a stable, universally responsive, and remarkably resilient governmental model. The federal government of the United States has withstood every abuse that power-hungry politicians could heap upon it over the past two hundred years! It has become bloated and distorted to the point where the Founders would be appalled to see it now, but it retains at its core that perfect model that Thomas Jefferson described as ideal. He called it a design for “a wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.”

After two hundred years of imperfect management, the American model still has produced a level of unprecedented individual prosperity. The U.S. Gross Domestic Product is now in the $20 trillion range, which is larger than the next three largest GDPs combined (China, Japan, and Germany). And of course, considering population differences makes our success even more dramatic. The median annual household income in the United States is just over $62,000, while in China it is about $1,100. In historical terms, modern middle-class Americans are as rich as once were kings.

The American Founders’ governmental design based on personal freedom and empowerment has been proven to be by far the greatest engine for producing the most prosperity for the greatest number that ever has been tried! That being true, it would be unconscionable for us not to be willing to to share it now. Let’s clean it up and tune it up, work out a few remaining bugs, and make it our gift to all the world!

The American people still retain the power to wrest control of their government back  from politicians who use dishonest tactics like inspiring righteous indignation to keep us at one another’s throats and distract us from their manifold failures! You and I can see past that now. Once we calmly demand all the facts about every issue in contention, the political charades that are currently tearing this nation apart are going to sputter and die. Then the people will be back in control. And once we have reclaimed our nation, we will be able to make of it the shining example to the world’s oppressed people that our Founders long ago hoped it would be. Then over time, with our help, all the people on earth can begin to live in their own free and prosperous republics based upon the only governmental model that ever has been shown to produce stability, prosperity, flexibility, resilience, and the protection of the weak against the strong.

from politicians who use dishonest tactics like inspiring righteous indignation to keep us at one another’s throats and distract us from their manifold failures! You and I can see past that now. Once we calmly demand all the facts about every issue in contention, the political charades that are currently tearing this nation apart are going to sputter and die. Then the people will be back in control. And once we have reclaimed our nation, we will be able to make of it the shining example to the world’s oppressed people that our Founders long ago hoped it would be. Then over time, with our help, all the people on earth can begin to live in their own free and prosperous republics based upon the only governmental model that ever has been shown to produce stability, prosperity, flexibility, resilience, and the protection of the weak against the strong.

The Founders very well understood that a free and empowered people were going to need a solid spiritual grounding. John Adams said, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious (sic) people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Benjamin Franklin said, “[O]nly a virtuous people are capable of freedom. As nations become corrupt and vicious, they have  more need of masters.” And Thomas Jefferson was two centuries ahead of his time when he said, “To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense that he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; & believing he never claimed any other.” It is those perfect non-religious teachings of Jesus that will provide the solid spiritual grounding that can make uniting all the world even possible.

more need of masters.” And Thomas Jefferson was two centuries ahead of his time when he said, “To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense that he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; & believing he never claimed any other.” It is those perfect non-religious teachings of Jesus that will provide the solid spiritual grounding that can make uniting all the world even possible.

Abraham Lincoln memorably said in the midst of a crisis that also split this nation, “We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.” Unless we will resolve to focus now on what is really important, and stop allowing political squabbling to keep splitting us apart over trivial nonsense, we are going to find it impossible to be of any use to a desperate world. So we have our work cut out for us! It is only all Americans together, reared from birth to be comfortable with personal freedom and empowerment, who have the means and the will to form that ultimate worldwide neighborhood. Billions of people are even now turning their hopeful eyes to us. And we can do this! Let’s roll!

photo credit: Jason K. Scott-Taggart <a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/49585574@N08/44970347131″>Brooklyn Bridge westward view New York 2001</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/”>(license)</a>