Posted by Roberta Grimes • January 25, 2014 • 0 Comment

Human Nature, Letters From Love Series, Slavery, Thomas Jefferson

Cultural realities shape our lives in ways that become so ingrained that we often don’t see evils for the evils they are. When you and I look around, we can see lots of things about  present-day America that are likely to appall our descendants, from overstuffed prisons and third-trimester abortions to vast disparities in wealth and station and the careless ways in which we inflict adult entertainment on our children. The fact that you and I don’t become personally involved in any of these practices doesn’t let us off the hook, since if enough of us protested, things would change.

present-day America that are likely to appall our descendants, from overstuffed prisons and third-trimester abortions to vast disparities in wealth and station and the careless ways in which we inflict adult entertainment on our children. The fact that you and I don’t become personally involved in any of these practices doesn’t let us off the hook, since if enough of us protested, things would change.

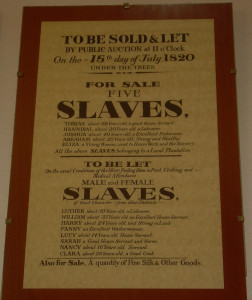

Thomas and Martha Jefferson were born into a world in which the slavery of peoples brought here from Africa had been part of their culture for a century. It was a normal evil, just as the things mentioned above are evils that seem normal to us. Having been born near the pinnacle of a society in which slavery was a fact of life, both Thomas Jefferson and Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson inherited human beings.

They were stuck with slavery. As Jefferson said later in life, they had a wolf by the ear: they could neither hold onto it nor safely let it go. And being freed was not an attractive option for a slave in Eighteenth-Century Virginia. It was legal at that time for anyone who encountered a freed former slave to enslave him again; and even beyond Virginia, freedmen lived wretched lives on the margins of white society. Discovering that Jefferson felt stuck with slavery as an institution that he detested was an important step for me, since I don’t think I could have written My Thomas if the truth were otherwise.

From my brief study of it, slavery in Eighteenth-Century Virginia seems surprising in a number of ways:

1) Apparently sexual relations between the races didn’t much occur before the middle of that century, so during Jefferson’s youth nearly all the slaves were of exclusively African ancestry.

2) Slaves apparently worked until dusk six days per week, but then typically had Sundays off. In Jefferson’s case, there is evidence that he often used Saturdays off as a reward.

3) During their free time, Jefferson’s slaves raised vegetables and chickens for themselves, and they sold their surplus food to their master for money. I know… I didn’t believe it either, but Jefferson’s written accounts of some of these transactions still survive.

3) During their free time, Jefferson’s slaves raised vegetables and chickens for themselves, and they sold their surplus food to their master for money. I know… I didn’t believe it either, but Jefferson’s written accounts of some of these transactions still survive.

4) Jefferson was set emphatically against the physical punishment of his slaves. His attitude seemed to be that he and they were stuck with this situation, so his only option was to care for them and treat them fairly. I was able to find just one instance of his ordering the whipping of a slave, and that was in his old age when apparently a teenager drove him temporarily insane. This incident upset him so much that it may have been the exception that proves the rule.

Martha Jefferson spent most of her life in the friendship of Betty Hemings, the half-white slave her father took to his bed soon after his third wife died. At his death, Martha inherited Betty and her children, six of whom were Martha’s half-siblings.

Thomas and Martha seem to have treated the Hemingses almost as part of their family. The love ran deep, and this difficult situation may have been one reason why Thomas Jefferson’s contemporary writings indicate an increasing impatience with slavery as an institution. He was too clear-headed and practical to think the problem would be easy to solve, but during  Martha’s lifetime he seems to have become increasingly determined to solve it. His first step was to engineer a ban on the importation of African slaves, and thanks to his efforts, in 1778 Virginia became the first place on earth to ban the importation of slaves.

Martha’s lifetime he seems to have become increasingly determined to solve it. His first step was to engineer a ban on the importation of African slaves, and thanks to his efforts, in 1778 Virginia became the first place on earth to ban the importation of slaves.

In 1781 Thomas Jefferson retired from politics altogether. Had Martha lived, he would have had the time to pursue the experiments in racial understanding and integration that were by then foremost in his mind. With his extensive political experience and skill, there is a reasonable chance that he would have been able to manage an end to slavery in America long before the Civil War. But when Thomas lost Martha, he seems to have lost his race-relations motor. He fled Virginia and the future they had planned together, and he tried to fill the void she had left by resuming his political career. It’s too bad, really. It’s difficult to read his Revolutionary-era writings on the subjects of slavery and race and not think about what might have been.