Posted by Roberta Grimes • July 15, 2014 • 0 Comment

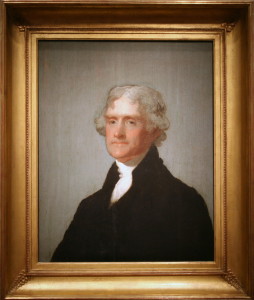

Slavery, Thomas Jefferson

My husband of forty-two years is a high-functioning Asperger’s person. Asperger’s Syndrome is a disorder on the autism spectrum whose sufferers tend to be very bright but often have trouble relating to others. A book published in 2000  called Diagnosing Jefferson makes a compelling case that our third president was another extraordinary man whose blessing and bane was Asperger’s Syndrome.

called Diagnosing Jefferson makes a compelling case that our third president was another extraordinary man whose blessing and bane was Asperger’s Syndrome.

The revelation that Thomas Jefferson’s life displayed the signs of Asperger’s is crucial for anyone who hopes to understand him. To ignore his condition and judge him for traits that were beyond his control would be as morally wrong as it would be to judge someone with a club-foot for his inability to run well. There are some advantages to Asperger’s Syndrome, but also some important disadvantages. I urge you to read Diagnosing Jefferson for a more complete analysis of all the ways in which the insight that our third President was an Asperger’s person helps us to make a better sense of him.

In particular, Jefferson’s Asperger’s diagnosis is helpful as we ponder his attitude toward race. It is clear from his writings that he hated slavery with the fervor of an ardent abolitionist.He well understood how incongruous it was for Americans to be fighting for their own freedom while they held a subject people in thrall, so in 1778, at the height of the American Revolution, he led a successful effort to make Virginia the first place on earth to end the importation of slaves. He saw this as a necessary step toward ending slavery altogether. There is little doubt that if his wife had lived, Thomas Jefferson would have retired from public life in 1781, and together they would have devoted the rest of their lives to finding a way to end slavery. But she died in 1782. And the idealist in her husband died with her.

Thomas Jefferson hated slavery, but he was also – how can I put this delicately? – convinced that there was a difference between the races. Unlike true racists, Jefferson did not want black people to be inferior to whites. This fear he had that there were racial differences enormously complicated his wish to free the slaves. But he believed to the end of his life that there were differences that went beyond shades of skin, and he believed this because he had Asperger’s Syndrome.

A key characteristic of Asperger’s people is a very much lessened or entirely absent ability to empathize with others. They cannot imagine that other people don’t see the world in the same way they do. This can be annoying in a marriage, although you learn to work around it. For a slaveholder, Jefferson’s inability to comprehend how different he might feel if he were a slave led him to draw disastrously wrong conclusions.

Thomas Jefferson was fourteen when his father died. Shortly before that event, something happened that forever shaped the boy’s perception of black people. Peter Jefferson was trying to rid his plantation of an old shed. He had a gang of slaves hauling on ropes, chanting as they were wont to do, and repeatedly failing to pull the thing down. Eventually Peter shooed the slave-gang away and took up the rope himself, and in front of his gullible son he singlehandedly pulled the shed down. Thomas Jefferson learned that day that his own father was physically stronger than four slaves pulling together.

As Martha discovers in My Thomas, this self-protective tendency of slaves to make as little effort as possible extended to intellectual matters as well. Her beloved Great George enlightens his mistress by telling her that a foolish man cannot survive as a slave. “The cleverest slave is the one most stupid. The quickest slave is the one most slow. If a slave can convince you he cannot work or his leg is lame or he has taken ill, then he has won, has he not? Only look at a slave and see a perfect idiot, and the man you see is surpassingly wise. The stupid ones you can work to death, mistress. The cleverest ones work the least of all.”

This made sense to Martha, who had the capacity to imagine how it would feel to be a slave. But Thomas Jefferson was an over-achiever with Asperger’s Syndrome. It seems never to have entered his mind that his slaves would not make the same effort to work and think that he did, so he saw their apparent weakness and dullness as a self-evident lack of capacity. To the end of his life he worried that black people were physically and mentally less than whites, so to free them into a stronger white culture would put them at a crippling disadvantage. He feared that racial differences might be so great that integration would be impossible, and a well-meant but ill-planned abolition could lead to bloody racial warfare and the tragic subjugation of the weaker race.

Thomas Jefferson was a realistic idealist. Before risking an emancipation that could be disastrous for this hopeful new nation and for the slaves themselves, he needed more information. Toward the end of Martha’s life he was thinking about  experimenting to see whether whites and free blacks could live in harmony on neighboring farms, but her death ended his interest in experimenting, as it ended his interest in many things.

experimenting to see whether whites and free blacks could live in harmony on neighboring farms, but her death ended his interest in experimenting, as it ended his interest in many things.

Last week I discussed the substantial evidence that it was Thomas Jefferson’s younger brother, Randolph, who fathered the children of Sally Hemings. To all of that we can now add the fact that a man as fastidious as Jefferson was, as obsessed with preserving his personal honor, and as worried that black people might be less than whites, would not have let himself father mixed-race children. With all the other evidence there is against the Thomas-Sally calumny, this certainty that Thomas Jefferson’s personality and beliefs would not have allowed a relationship between them is something you can take to the bank.