It doesn’t matter to me who fathered Sally Hemings’s children. Seeing how devastated Thomas Jefferson was by  the death of his wife at thirty-three, at one time I even thought that if he had managed to find a new love later in life, that was fine and none of us had the right to judge him for it. But knowing Jefferson as I had come to know him, I became sadly confident that it never had happened. Seeing that his nephews, the Carrs, seemed to have fessed up to it, at the last minute I added to the 1993 edition of My Thomas a postscript naming one of them as the father of Sally Hemings’s children. Then after the novel was first published I did some more extensive research. I came to see that all the evidence pointed not to Thomas Jefferson and not to the Carrs, but to Thomas’s younger brother, Randolph.

the death of his wife at thirty-three, at one time I even thought that if he had managed to find a new love later in life, that was fine and none of us had the right to judge him for it. But knowing Jefferson as I had come to know him, I became sadly confident that it never had happened. Seeing that his nephews, the Carrs, seemed to have fessed up to it, at the last minute I added to the 1993 edition of My Thomas a postscript naming one of them as the father of Sally Hemings’s children. Then after the novel was first published I did some more extensive research. I came to see that all the evidence pointed not to Thomas Jefferson and not to the Carrs, but to Thomas’s younger brother, Randolph.

It has been twenty years since I researched the Sally Hemings question, soon after My Thomas first was published. The evidence that it was Randolph and not Thomas who had had a relationship with Sally Hemings seemed so incontrovertible to me that I am astonished that the old story has not long since been widely seen as discredited. For example:

1) A relationship could not have begun in Paris. Thomas Jefferson went to Paris as a widower with his oldest daughter in 1784, and he sent for his middle daughter after the youngest died at Monticello. Fourteen-year-old Sally Hemings accompanied that second daughter to Paris in 1787, but she was a last-minute choice that probably was made at Monticello. It seems unlikely from the evidence that Sally’s going to Paris was Jefferson’s idea. I have seen it suggested that Paris was where he began a relationship with Sally, but there was no contemporary whisper of it. And Sally didn’t return from Paris pregnant, nor did she become pregnant soon thereafter. Her first child wasn’t born until she was twenty-two years old.

2) Randolph was reportedly often at Monticello when his brother Thomas was there. Randolph’s plantation was twenty miles from Monticello, and contemporary accounts suggest that he was a frequent visitor.

3) Randolph socialized with the Monticello slaves. It was said that he was often in the quarters and he would “play the fiddle and dance half the night.” His brother Thomas, on the other hand, is not reported to have socialized in the quarters at all. My extensive reading of his early correspondence indicates that the young Thomas Jefferson hated the institution of slavery and considered the fact that he had inherited slaves and there was no legal or practical way to free them to be a bane and a burden.

4) Sally’s Jefferson children were conceived during the interval when Randolph was single. Randolph was widowed young, and in defiance of custom he did not soon remarry. By my calculation, all of Sally’s Jefferson children were fathered while Randolph was single. I further have seen evidence that Randolph’s relationship with Sally was known among the slaves, who on at least one occasion saw him sneaking from Sally’s cabin early in the morning.

5) Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings were together in the same house for two decades without more children. Sally’s last Jefferson child was conceived in 1807, when she was only 33 and shortly before Randolph ventured west. Jefferson lived for nearly twenty years more, and during all that time Sally Hemings served as a Monticello house servant. If her Jefferson children were Thomas’s and not Randolph’s, why on earth did she stop bearing them so young?

6) There are no reports that Thomas Jefferson took a special interest in Sally Hemings. I have seen no contemporary reports that anyone saw affection between them. Although he freed her children, he did not free Sally at his death. Given the decades during which they lived in close proximity in a house full of servants, and given the fact that Sally bore six Jefferson children (four survived), this lack of contemporary evidence of an apparent relationship between them seems to me all by itself to be a full refutation of the rumor.

7) The story that Sally Hemings bore Thomas Jefferson’s children is rooted in vitriol. The only contemporary evidence that Thomas Jefferson might have been the father of Sally Hemings’s children was the word of a reprobate named James T. Callendar whom Jefferson had denied an appointment as the Postmaster of Richmond, Virginia, and who bore the then-president a public grudge.

8) There is no other evidence of a Thomas-Sally relationship. Those seeking to advance the notion that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’s Jefferson children have nothing but Callendar’s attacks to rely on, so they have advanced what they call additional evidence. All of it is speculative in the extreme. For example, Jefferson took measures to screen his private rooms from outside view when he returned to Monticello following his presidency. It has been suggested that he was seeking to hide a relationship with Sally, but this action of his has a simple explanation rooted in colonial custom. It had long been usual for travelers on the road to stop for the night at plantations on the way, and so many people took advantage of that fact and arranged to be near Monticello at nightfall so they could become the former president’s overnight guests that in Jefferson’s old age his Monticello became a kind of unpaid hotel. With so many strangers wandering his grounds, it is not surprising that a man so private wanted to keep people from looking in at him.

9) Thomas Jefferson’s personality and character make such a relationship unlikely. Eighteenth-century gentlemen thought very differently from people living today. It is easy for us to say that, what the heck, Sally looked like Thomas’s late wife and she was his property, so naturally he would have had his way with her. But gentlemen in his day were obsessed with guarding their honor, and Thomas Jefferson was fastidious about this to a fault. His extensive writings make it seem unlikely that he was capable of thinking as we do. And even though in many ways he was a different man after Martha’s death, I think the fact that Sally was his property – in the absence of any other good evidence – is thin justification for deciding that therefore he must have been the father of her children.

10)Thomas Jefferson had emotional issues that make his having been the father unlikely. He seems to me to have been emotionally incapable of fathering mixed-race children. There, I’ve said it. My reasons for feeling so strongly about this are going to have to wait for next week’s blog post, but when you see my reasoning I think it will make sense to you.

10)Thomas Jefferson had emotional issues that make his having been the father unlikely. He seems to me to have been emotionally incapable of fathering mixed-race children. There, I’ve said it. My reasons for feeling so strongly about this are going to have to wait for next week’s blog post, but when you see my reasoning I think it will make sense to you.

So Thomas Jefferson is very unlikely to have been the father of Sally Hemings’s children.We are not going to know the truth until each of us eventually dies and thinks to investigate the Sally Hemings question from where the truth resides. For now, I think there is enough evidence that somebody else fathered Sally Hemings’s children that with all that Thomas Jefferson did for his country, the benefit of the doubt is the least that we owe him.

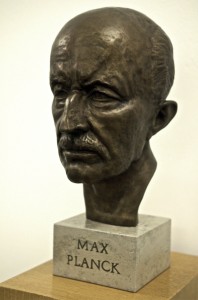

are immensely entertaining. I began reading popular science a couple of decades ago as I tried to puzzle out the physics of the realities into which we graduate at death. What I learned was that many of the peculiarities of physics in the greater reality can be nicely explained once you have even a nodding acquaintance with quantum physics. I learned a lot more as well. And sadly, the more I learned about the issues that torment mainstream scientists now, the more I began to see how in nearly every case I was able to offer insights and explanations that came from my study of the afterlife evidence. Mainstream science has been off the rails and into the weeds for the past century because it still refuses to consider all the implications of quantum physics.

are immensely entertaining. I began reading popular science a couple of decades ago as I tried to puzzle out the physics of the realities into which we graduate at death. What I learned was that many of the peculiarities of physics in the greater reality can be nicely explained once you have even a nodding acquaintance with quantum physics. I learned a lot more as well. And sadly, the more I learned about the issues that torment mainstream scientists now, the more I began to see how in nearly every case I was able to offer insights and explanations that came from my study of the afterlife evidence. Mainstream science has been off the rails and into the weeds for the past century because it still refuses to consider all the implications of quantum physics.

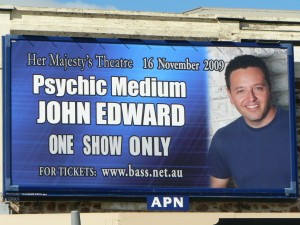

twentieth-century deep-trance mediums who were able to withdraw from their bodies altogether and allow their dead controls to speak using the medium’s vocal cords. There were some amazing deep-trance mediums working in the early twentieth century, and if the evidence of our survival produced by even one of them – Leonora Piper, perhaps, or Gladys Osborne Leonard – had been objectively studied by contemporary scientists, you would have lived your whole life knowing that it never is going to end. They produced such consistent and extensive proofs of what actually is going on that eventually they convinced even me. But, mediums reading the minds of the dead? Not so much.

twentieth-century deep-trance mediums who were able to withdraw from their bodies altogether and allow their dead controls to speak using the medium’s vocal cords. There were some amazing deep-trance mediums working in the early twentieth century, and if the evidence of our survival produced by even one of them – Leonora Piper, perhaps, or Gladys Osborne Leonard – had been objectively studied by contemporary scientists, you would have lived your whole life knowing that it never is going to end. They produced such consistent and extensive proofs of what actually is going on that eventually they convinced even me. But, mediums reading the minds of the dead? Not so much. Gospel words of Jesus or the afterlife evidence, I think it may be time for us to consider the possibility that Jesus’s mission may have been different from the one assigned to him by mainstream Christianity.

Gospel words of Jesus or the afterlife evidence, I think it may be time for us to consider the possibility that Jesus’s mission may have been different from the one assigned to him by mainstream Christianity.

mainstream Christianity is wrong. I have never in decades of reading hundreds of communications from the dead found any evidence at all that God or any religious figure ever has judged anyone. Neither have I ever found an instance where a dead person says or hints that the death of Jesus redeemed him from punishment for his sins. So Christianity is wrong about that. It’s wrong.

mainstream Christianity is wrong. I have never in decades of reading hundreds of communications from the dead found any evidence at all that God or any religious figure ever has judged anyone. Neither have I ever found an instance where a dead person says or hints that the death of Jesus redeemed him from punishment for his sins. So Christianity is wrong about that. It’s wrong. remain skeptical of every new afterlife-related detail, but at least I do investigate things! I look for answers. And after I have assembled enough evidence of all stripes to draw a rational conclusion, I draw that conclusion and explain where it came from. What these scientific Luddites do is to refuse to investigate anything that doesn’t fit their predetermined beliefs. They even presume to post on the Internet flat lies about the afterlife evidence and about those who would investigate the evidence. Have they no self-awareness at all?

remain skeptical of every new afterlife-related detail, but at least I do investigate things! I look for answers. And after I have assembled enough evidence of all stripes to draw a rational conclusion, I draw that conclusion and explain where it came from. What these scientific Luddites do is to refuse to investigate anything that doesn’t fit their predetermined beliefs. They even presume to post on the Internet flat lies about the afterlife evidence and about those who would investigate the evidence. Have they no self-awareness at all? core creative force and the only reality. All of this is as scientific as anything could be scientific, and it is at the core of what we all should be thinking as we study reality.

core creative force and the only reality. All of this is as scientific as anything could be scientific, and it is at the core of what we all should be thinking as we study reality.