I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

– Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) from “Ozymandias” (1817)

New Scientist is a British popular science magazine that I find adorable. It is charming and plucky and delightful in the same way that a bright but blind and deaf child might be: not entirely functioning, true, but always determined despite its limitations to do its utmost best. I read New Scientist always knowing that if only those earnest but blind-and-deaf scientists could see and hear what I can see and hear, they would run rings around me a hundred times over!

New Scientist is a British popular science magazine that I find adorable. It is charming and plucky and delightful in the same way that a bright but blind and deaf child might be: not entirely functioning, true, but always determined despite its limitations to do its utmost best. I read New Scientist always knowing that if only those earnest but blind-and-deaf scientists could see and hear what I can see and hear, they would run rings around me a hundred times over!

This sense I often have that my beloved little mag that tries so hard could do wonders if only it could properly function was triggered in force by its November 20th edition. The title was simply, “Why?” And on its cover it asked thirteen basic questions that ranged from Why do we exist? And Why is there something and not nothing? Down to Why are we conscious? Why does time only move forward? and Why is the universe just right? If I had been an editor, I also would have wanted to ask Why is there all this dark matter and dark energy? But perhaps that’s a question still beyond the pale, when there really isn’t even yet a reasonable matter-based approach to answering it.

Of course, the scientists published in New Scientist are neither blind nor deaf. They are just self-handicapped by their decision to work as part of the resolutely blind-and-deaf scientific research community. To do that requires, even to this day, that they obey the fundamental dogma of materialism; and that means that every popular-science publication is still to some extent a humor magazine. To read scientific articles and come across problem after problem that even I can solve is laughable! But still, those of us who are free to do open-minded research have been able to do a great deal of building on what little the dogma-hobbled mainstream research scientists have been allowed to do, and then to share. And also, of course, this past century has been a heyday of matter-based technological research, which has had a free and fabulous hundred-year run. Only look at the fact that billionaires can now confidently talk about colonizing Mars, and you know that matter-based technology is indeed the science of the future!

But those who have chosen to chase Nobel Prizes as research physicists and astronomers have had a pretty dismal century. The materialist dogma that was imposed on them just over a hundred years ago has reduced them to doing the equivalent of trying to study just the walls and floor of a room, having had the ceiling declared off-limits because it is composed of a material which just arbitrarily cannot be considered; and then, if they hope to make a living, they must stolidly spend their entire careers in attempting to determine what might be the source of all that water on the floor. Therefore, we get scientists who are repeatedly forced to scratch their heads over inexplicable findings, like a universe that keeps behaving nonsensically.

But those who have chosen to chase Nobel Prizes as research physicists and astronomers have had a pretty dismal century. The materialist dogma that was imposed on them just over a hundred years ago has reduced them to doing the equivalent of trying to study just the walls and floor of a room, having had the ceiling declared off-limits because it is composed of a material which just arbitrarily cannot be considered; and then, if they hope to make a living, they must stolidly spend their entire careers in attempting to determine what might be the source of all that water on the floor. Therefore, we get scientists who are repeatedly forced to scratch their heads over inexplicable findings, like a universe that keeps behaving nonsensically.

Just over a hundred years ago, the university departments and the peer-reviewed journals chose to codify into a dogma what had been an informal separation between material and non-material fields of inquiry going back as far as Plato and Aristotle. They instituted “the scientific dogma of materialism.” And yes, at the time you could find those words in print. Adopting a dogma made sense, of course, back twenty-five hundred years ago when you were first trying to separate out your earliest attempts to make sense of the material world from the prehistoric religions that humans had invented as a bulwark against their superstitious fears. Back then, nothing was understandable and everything was magical, and placating the gods that we ourselves had created was our one slender hope against the wailing dark. But in about the 1600s came the dawning of the Age of Enlightenment, which was an intellectual and philosophical movement that gave birth to a flowering of good ideas as varied as modern scientific inquiry and our American Declaration of Independence.

New Scientist’s answers to its Why? issue’s questions are as pathetic as you might expect them to be, given their source in a willfully clueless tribe. In fact, any well educated and open-minded researcher could answer most of those cover questions with one word:

New Scientist’s answers to its Why? issue’s questions are as pathetic as you might expect them to be, given their source in a willfully clueless tribe. In fact, any well educated and open-minded researcher could answer most of those cover questions with one word:

CONSCIOUSNESS

If you had allowed the scientists trying to answer those thirteen questions to consider consciousness as the base creative force, then most of their questions would have been answered easily. In perfect fact, it’s simply extraordinary! It’s like solving for a kind of ultimate prime number that unlocks all the keys to reality. You free scientists to study consciousness, and suddenly even a lot of seemingly unrelated factor come together and make sense. But when you insist that what is obviously primary is just an artifact of the human brain, you create nonsense on a massive scale. Our dear New Science cannot even define consciousness! It calls it “something it is like to be,” which somehow arises in the brain. New Scientist has trouble defining reality, too, which ought to be more of a red-flag for them than it is. Prior to The Age of Enlightenment, the Catholic Church held a similar dogma-based sway over all scientific inquiry. And its deist dogma held intellectual progress stuck in time until the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s. Indeed, it is not at this point a stretch to look forward to the Second Age of Enlightenment of the Twenty-Second Century that will follow this current period of protracted dogma-enforced scientific darkness.

In point of fact, that materialist dogma has already caused incalculable pain. It is one thing for scientists to have to keep fudging their supposed cosmological “constants” (link), or for their lack of curiosity about 95% of what exists to mean that the universe is going to keep perplexing them. But to this day, their dogma requires that human consciousness dies when the body dies, so they impose a ghoulish fatalism on humankind that weighs us down in ways that are going to require that Second Reformation once the long night of gloomy negativity that mainstream science is determined to impose on us ends.

In point of fact, that materialist dogma has already caused incalculable pain. It is one thing for scientists to have to keep fudging their supposed cosmological “constants” (link), or for their lack of curiosity about 95% of what exists to mean that the universe is going to keep perplexing them. But to this day, their dogma requires that human consciousness dies when the body dies, so they impose a ghoulish fatalism on humankind that weighs us down in ways that are going to require that Second Reformation once the long night of gloomy negativity that mainstream science is determined to impose on us ends.

And it’s amazing how fiercely the scientific community continues to actively fight the possibility that human life continues after physical death! as recently as 2016, New Scientist did a whole special issue on death without considering the possibility that anything might follow it. And in 2020, it did an article suggesting that the only possible kind of immortality would require artificially preserving some aspects of a dead person’s personality. Even Bill Nye the Science Guy has just weighed in against even the possibility of an afterlife, despite the fact that any actual scientist could tell him its impossible to prove a negative.

It’s time to say this bluntly. The mainstream scientific materialist dogma that has kept hidden for a further century the fundamental truth about humankind’s glorious eternal natures is worse even than anything that any religious dogma ever has imposed on the world. As I will try to demonstrate to you next week.

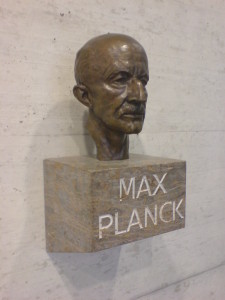

And it didn’t have to be this way! Some of the greatest scientific thinkers of the twentieth century knew or strongly suspected that quantum mechanics had revealed that there was a great deal more to reality than what a study of matter alone could reveal. And they said so! If only the wisdom of our greatest scientists had been given even passing consideration!

In 1931 Max Planck said, “I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.”

In 1931 Max Planck said, “I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.”

And Nikola Tesla, who always got right to the point, wisely said, “The day science begins to study non-physical phenomena, it will make more progress in one decade than in all the previous centuries of its existence.”

What the scientific gatekeepers should have done was to skip all their faculty-lounge debating and just kept their fingers off the scale! Why were they so afraid to let their truths fight it out in the free arena of ideas? Let the truth about consciousness, death and the afterlife, whether there might be some creator, and who and what human beings actually are gradually fight it out with the help of the greatest scientific minds immersed in research and free of all constraints, over what could have been a very productive and not a wasted century. Every truth in the end must eventually rise or fall on its actual merits alone! This hundred-year detour into the scientific weeds didn’t have to happen, to humankind’d great detriment. Eventually, the truth is going to win. And the longer they wait to be open about their obfuscations, the worse their reckoning is going will be.

I might add that I have never before disputed Thomas’s frame-verse choices, but I was shocked by this one. Humiliating the pretentious is not our style! But he said that Shelley wrote his poem for precisely this situation, as a mirror for fools who think they can impose their self-important ignorance on the world. I suppose that to people who are still alive but are being summarily dismissed as dead, this fight with modern scientific cluelessness might feel like a personal grievance.

I might add that I have never before disputed Thomas’s frame-verse choices, but I was shocked by this one. Humiliating the pretentious is not our style! But he said that Shelley wrote his poem for precisely this situation, as a mirror for fools who think they can impose their self-important ignorance on the world. I suppose that to people who are still alive but are being summarily dismissed as dead, this fight with modern scientific cluelessness might feel like a personal grievance.

I blurted to him, “What? Do you know Shelley personally?” After all, they were earthly contemporaries! But he just smiled.

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

– Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) from “Ozymandias” (1817)